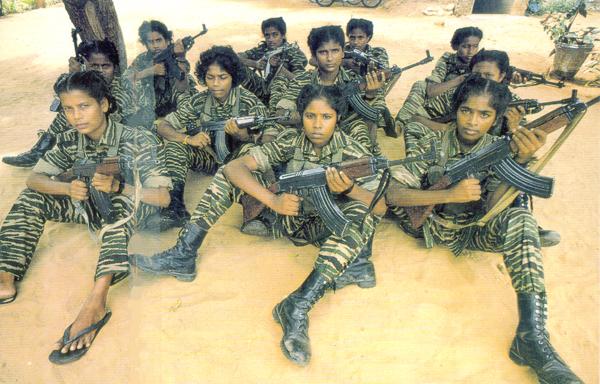

Tamil women’s oppression post-2009 is in stark contrast with Tamil women’s liberation with the LTTE, as shown in this image.

Image Source: http://www.eelamview.com/2013/07/29/women-under-ltte-cannon-fodder-or-womens-liberation/

Written By: Jessica Chandrashekar and Roshni Raveenthiran

The following is a discussion that emerged out of a conference that dealt with questions of feminisms and structural violence in contexts of war, authoritarianism and genocide. We focus on the presentation that Tasha Manoranjan gave titled “Gendered Genocide: Sri Lanka’s War Against Tamils”.

The purpose of this piece is to share what we learned from Tasha’s talk, as well as our thoughts on structural violence and the Tamil genocide. By naming violence as ‘structural’ we are showing how violence is more than just one individual harming another individual. Violence is made possible and enabled by institutions such as the legal system, the state and the media. These institutions are created or structured so that some people gain certain privileges and protections, while other people are oppressed.

We want to open up a discussion about the structural dynamics of the Tamil genocide. We feel that this discussion is important and necessary, particularly in our current context. In this current moment the UN OISL is writing their report and will make recommendations to the international community; there are debates on dropping the term ‘genocide’; and Eezham Tamils- particularly those in the Vanni, are struggling against colonization and military occupation.

The month in which we began our discussion is significant because our conversations on structural violence and the Tamil genocide took place during November. November is the month of Maaveerar Naal, a day of remembrance of those who sacrificed their lives for the freedom and liberation of Eezham Tamils. As such, we discussed three questions and below we share with you our collective thoughts.

1. “What is structural violence and how is the Tamil genocide structural?”

1. “What is structural violence and how is the Tamil genocide structural?”

Jessica: Structural violence is a form of violence that oppresses people as members of a group. The oppression of people as a group is made possible because of the way a society is organized, or in other words, structured. In the case of the Tamil genocide, we can see the ways in which the state of Ceylon, and later Sri Lanka, has created laws and policies over several decades that not only oppress Tamils, but seek to destroy and eradicate their existence. In fact, it was the structure of the Sri Lankan state that led to the armed struggle led by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE).

Roshni: The structural violence of the Sri Lankan state, and by extension, the Tamil genocide, is gendered. This means that the violence of genocide has had particular effects on women. In her presentation, Tasha Manoranjan referred to the case of Krishanthi who in 1996 was raped and killed while she was passing through an army checkpoint in Jaffna. Her mother, brother, and a neighbour were also killed when they tried to help 18-year old Krishanthi. The Krishanthi case also shows how the checkpoints created a network of violence and an atmosphere of fear. This fear had widespread societal impacts, such as young women being too fearful to go to school because they had to cross through the checkpoints on a daily basis. This had gendered implications, for example by limiting access to education for fear of sexual violence at checkpoints.

Jessica: I agree, this example shows how the Tamil genocide works to terrorize Tamils through violence against women. It also shows how the state is structured to carry out genocide- this is not an example of a few rogue army men. Rather, the role of the checkpoints and the army serving at these points was to instill fear within the general Tamil population. The murder of Krishanthi, her mother, brother and neighbour were made possible because of how the state, which in this case takes the form of the army and their checkpoints, views Tamils.

2. “How does genocide work through gender? How does the destruction of a nation work through the oppression of the nation’s women?”

Roshni: Genocide manifests and operates through violence against women who belong to the group that is targeted for destruction. The specific targeting of women is often because of women’s roles as the protectors and reproducers of the nation and national identity. Manoranjan described Tamil society prior to the war where Tamil women’s bodies represent Tamil national identity, so when the Sri Lankan army targets their bodies through sexual violence, they are also targeting the Tamil nation as a whole. In fact, this is a form of genocide as defined by the Genocide Convention.

Jessica: This is true and the situation is the same or even worse after May 2009*. Tamils are living under army occupation of their homeland. There has been a sharp increase in violence against Tamil women who are now forced to live in one of the most militarized regions in the world. Tasha listed several examples of genocide through violence against Tamil women such as the practice of forced sterilization of Tamil women in the Northern Province. Compare this with another state program where Sri Lankan army officers and police are given 100,000 rupees if they have a third child. These examples are revealing because they show explicitly how Eezham Tamil women are literally being prevented from bearing the next generation of Tamils, while the army and police are being rewarded for having children.

3. “How might we remember our martyred sisters, and how might we struggle in solidarity with our sisters who are currently living under Sri Lankan occupation?”

3. “How might we remember our martyred sisters, and how might we struggle in solidarity with our sisters who are currently living under Sri Lankan occupation?”

Jessica: What I found to be so important was when Tasha described how gender equality was built in the state of Eelam and also within the movement. Women LTTE cadres challenged many gender roles, through determination and hard work. Women cadres pushed their physical limits and matched the strength of their male counterparts. Through women’s leadership, the LTTE opened up many opportunities for Eezham Tamil women.

Roshni: Some of the opportunities and achievements that Tasha observed was how the LTTE promoted women’s education and abolished the dowry system. Women’s equality was established through these policies and Tamil women were able to thrive and live in a safe society where they had control over their bodies and their futures. This is in drastic contrast to the context described in the Krishanthi case, as well as today’s post-2009 situation.

Jessica: Women LTTE fighters showed bravery on the battlefield and often risked their lives to retrieve their martyred comrades. I was so affected by the quote Tasha shared from one of her interviews

“One female LTTE cadre, Vengai, described to me the strict policy of never leaving a fallen cadre’s body behind. She remarked, ‘It is worth risking my life to save the lifeless body of another female cadre…. It would be easier to accept my own death, than the mutilation of their bodies and spirits.’

Dsiclaimer: All views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect www.tamilyouth.ca’s views and opinions.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

Tasha Manoranjan is the founder and director of People for Equality and Relief in Lanka (PEARL), a non-profit advocacy organization dedicated to promoting human rights in Sri Lanka. She spent over a year documenting human rights violations committed against Tamil civilians in Northern Sri Lanka, and remains committed to pursuing accountability for violations of international law. Tasha earned her law degree from Yale Law School.

Jessica Chandrashekar is a doctoral candidate in the Gender, Feminist and Women’s Studies program at York University. Jessica uses an anti-colonial feminist framework to examine the Tamil genocide. While paying particular attention to the post-2009 period, Jessica situates her work within a post-colonial genealogy of Sri Lankan state violence.

Roshni Raveenthiran is currently majoring in her B.A Psychology and obtaining her South Asian Studies certificate at York university. Roshni is the current executive for the York University Tamil Students’ Association. She hopes to obtain her counselling degree in order to help domestic violence survivors, specifically within the Tamil community.

Tags: Tamil History/Culture